By Hritik Bhatnagar

Tucked amidst the dense mosaic of forests and fields in Bastar’s Tokapal block lies Kamdeo Kurushpal—a small Gond Adivasi village with a big vision. For decades, this small village lived in the shadow of colonial-era forestry practices, where monoculture plantations of Acacia auriculiformis replaced vibrant native forests. But with the recognition of their Community Forest Resource (CFR) rights in 2022, the villagers have set in motion a quiet revolution in forest restoration—one rooted in traditional knowledge, community labor, and long-term stewardship.

A Village’s Struggle with Monocultures

The story of degradation in Kamdeo Kurushpal mirrors that of many Adivasi villages in central India. By the 1990s, much of the native forest was cleared—some due to ceremonial use, some out of daily necessity in the absence of alternatives. In its place, the Forest Department planted fast-growing acacia to meet timber targets. “This forest is no longer ours,” says Maya Ram, a village elder. “We want the forest to be how it was before. The earlier forest was for our use, but now even farming is hard because of these plantations.”

Villagers recall a once-diverse forest that included trees like Mahua, Sal, Bija, Char, and Adan, all of which supported local culture, food systems, and seasonal livelihoods. Over time, these were replaced by dense acacia and eucalyptus groves that offered little more than firewood, degraded soil, and reduced water availability. “The cattle don’t even go in anymore,” Maya Ram adds. “The forest has become too dense, and there’s no space for grazing.”

The Fight for CFR and a Vision for Restoration

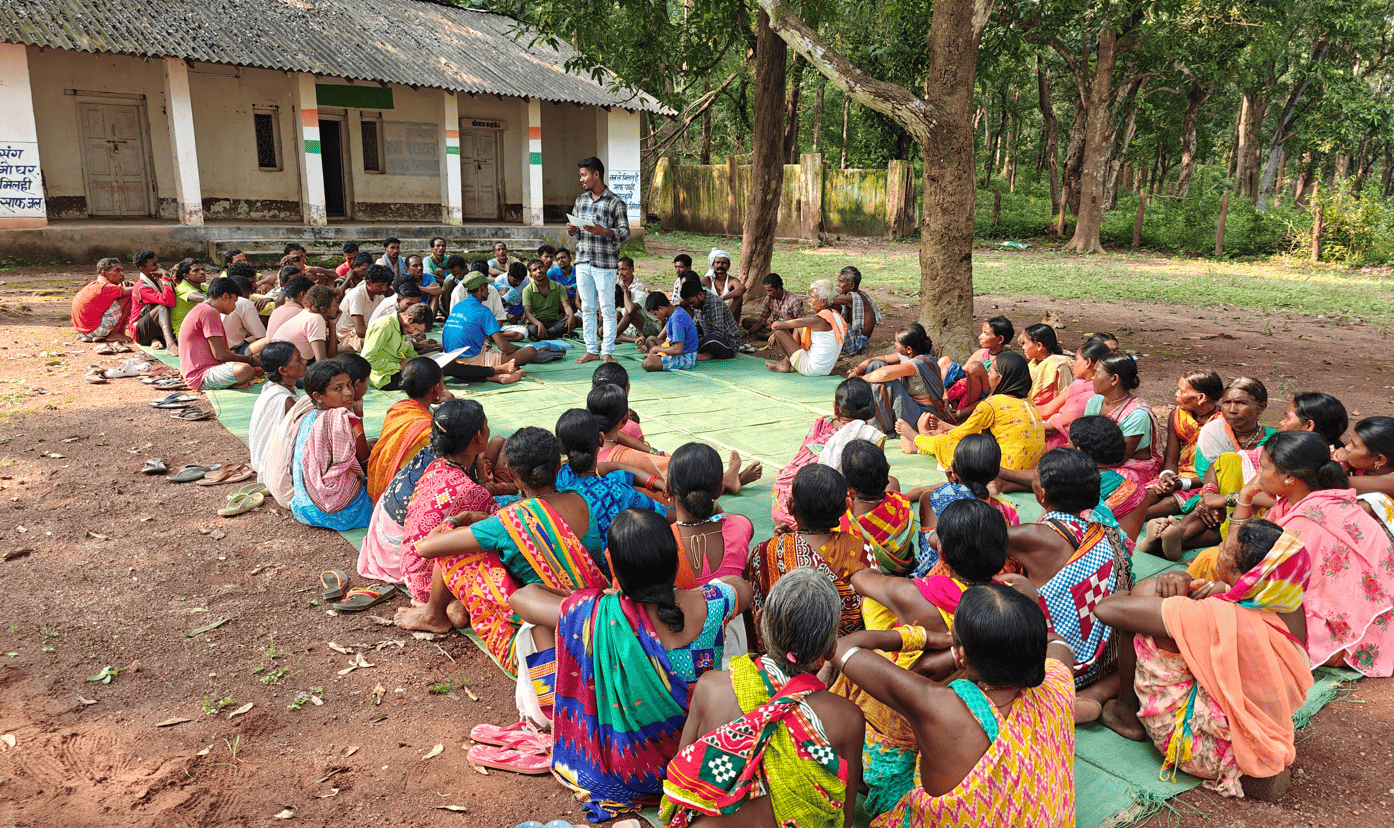

In 2019, a group of youth, including Rupchand Nag and his cousin Anil, began studying the Forest Rights Act of 2006. They initiated the CFR claim process with the support of elders, women, and other youth. After facing multiple roadblocks—including a delay at the sub-divisional level and a boundary dispute with neighboring villages—the village finally received its CFR title in December 2022. A steel company’s attempted land grab further galvanized the community, leading to a successful protest and reassertion of Gram Sabha authority.

Since then, Kamdeo Kurushpal has not only protected its forests but taken proactive steps to revive its ecological heritage. In early 2024, the Gram Sabha developed and submitted a Forest Management Plan, prioritizing the reintroduction of native species and gradual replacement of invasive lantana and siam weeds. A 5.7-hectare area was mapped for plantation in two phases, with the first 3 hectares planted in 2024 and the remaining 2.7 hectares scheduled for 2025.

Reviving Mahua and Other Native Trees

The plantation effort in 2024 saw the planting of 613 saplings—over 450 of them Mahua, alongside Jamun, Belwa, Tamarind, Mango, and Hirda. The saplings were sourced from the Jagdalpur Horticulture Department, and about 512 were still thriving as of May 2025, reflecting a strong survival rate of 83.5%.

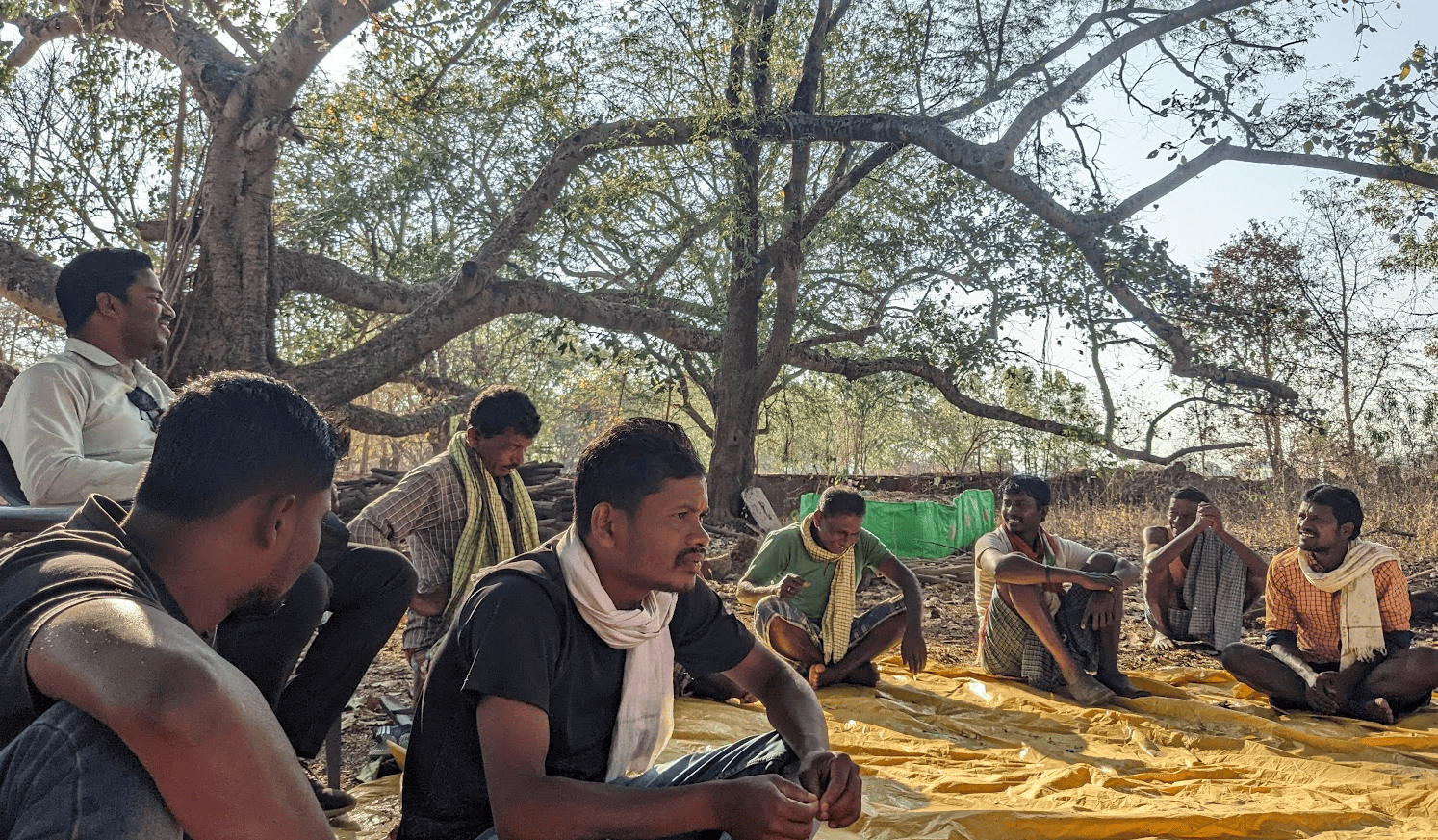

Crucially, this wasn’t a project driven by outside contractors or NGOs—it was a people’s effort. Every household contributed through shramdaan (voluntary labor). Women dug the pits, men planted the saplings, and collectively they installed a 500-meter water pipeline from a nearby rivulet with financial support for materials provided by ATREE. A water storage structure was also constructed with local oversight.

Daily patrolling is now undertaken through a rotational system called thengapali, with each household taking turns. A ₹300 fine for non-attendance ensures accountability. This collective ethic has also extended to neighboring villages, with Kamdeo Kurushpal becoming a resource hub for CFR processes. Rupchand and others have supported CFR claims in villages like Mavleebhata, Nainnar, and Kalepal—the latter already receiving their title.

Challenges Ahead and Community Resilience

Despite these gains, challenges remain. The plantation site still faces occasional cattle damage, especially from livestock belonging to other villages. Temporary fencing made of acacia branches has proven inadequate, leading the Gram Sabha to plan for more durable wire fencing in the second phase. Monitoring, though conducted through daily patrols, lacks standardized documentation methods such as photo-points or GIS-based tracking.

Yet the resolve is evident. “We want our forest to reflect our needs, our culture, and our livelihoods,” Rupchand explains. “We don’t want just firewood—we want Mahua, Kaju, Sal, and water security.” Plans are also underway to curb eucalyptus plantations on private land, remove invasive species like Lantana and Siam weed, and expand livelihood options through government schemes.

What’s striking is the shift in mindset. The villagers no longer think of their forest as a collection of trees but as an integrated landscape. They speak of multi-year planning, ecological balance, and intergenerational justice. For them, reclaiming the forest is about reclaiming their future—culturally, economically, and politically.

A Model for Other Villages

Kamdeo Kurushpal’s story is not unique—but it is exemplary. It shows how grassroots action, when backed by legal rights and collective will, can undo decades of top-down ecological mismanagement. It also shows that forest restoration is not a technical exercise—it’s a social process rooted in memory, identity, and vision.

The saplings planted today in Kamdeo Kurushpal may take years to mature, but they already embody something far deeper: the regeneration of agency and hope in a village that once felt it had lost their native fauna. With each Mahua that survives, a piece of the past is reclaimed—and a seed for the future is sown.