By Supreetha Devarakonda

This is a draft of the manuscript under review for Forests, Trees and Livelihoods (Taylor & Francis).

Walking through the haat, the weekly market in Kodenar, in Bastar district of Chhattisgarh, one notices rows of tarpaulin tents. Under each tent is a trader seated on a chair with helpers beside him. He weighs and purchases bags of agricultural and forest produce brought in weekly by villagers in the vicinity. Towering piles of peeled tamarind, impressive heaps of millet line the lane, along with modest mounds of Mahua – the flowers of the Madhuca latifolia tree. Eedu or irpool for the local Gond and Dhurwa tribes or Adivasis. But these mounds may not have always been so modest, suggesting a decline in yield. What has caused this?

Literature from over a decade ago reflects Mahua’s centrality in Adivasi life and documents long-standing concerns around distress sales and dwindling production in Chhattisgarh (Panda et al., 2010). Yet, recent work on how these discourses have evolved is scarce. In the summer of 2024, I set out to explore this gap for my Master’s thesis, in the context of Bastar.

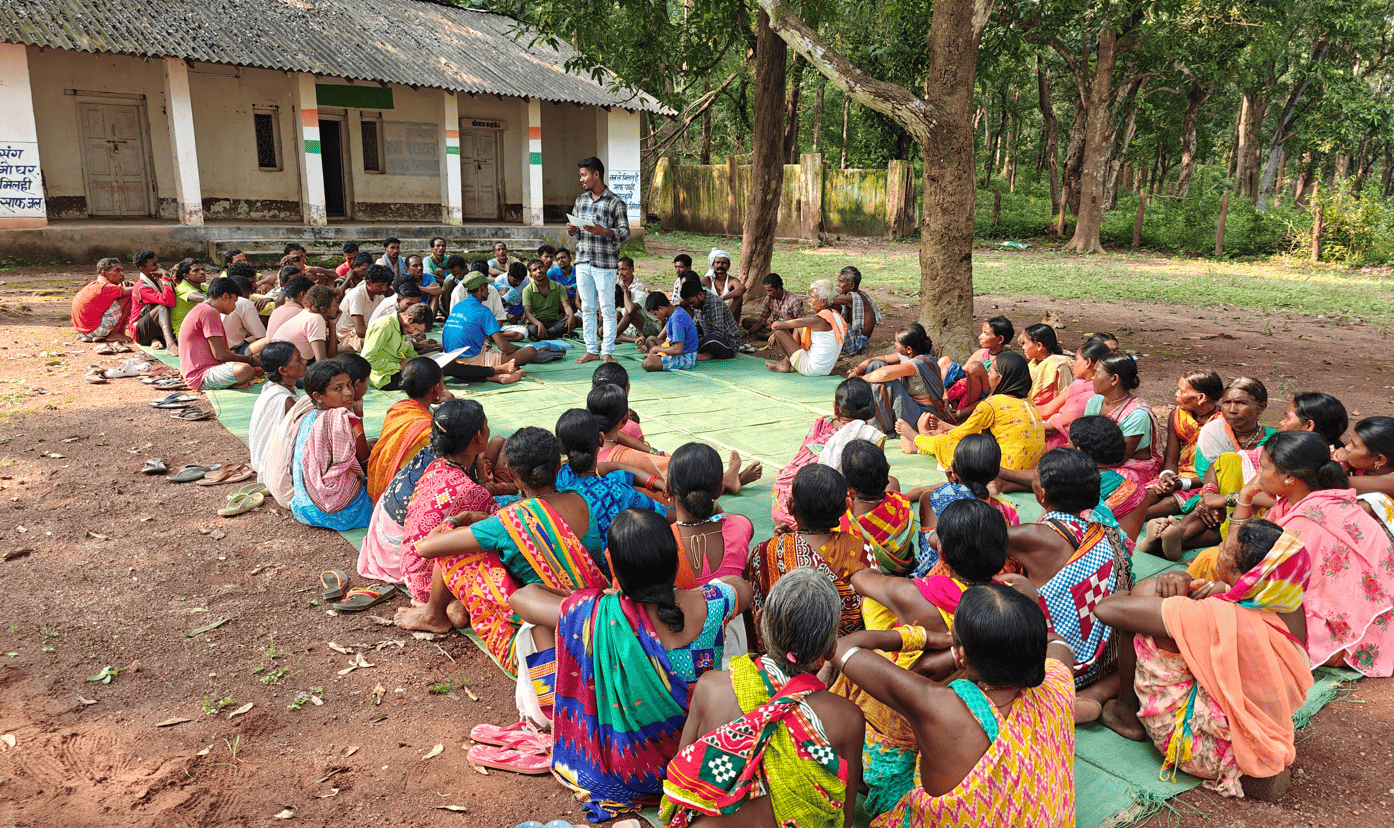

Field observations in villages and haats, combined with conversations with over a hundred people–the Adivasi residents of Badekakloor, Gumalwada and Nagalsar, traders, and other stakeholders, form the foundation of this study. Together, they reveal a complex picture of Mahua’s cultural, ecological, and economic role, and the emerging challenges of sustainable livelihood governance in Chhattisgarh. This short research note reflects on the current state of Mahua use, the marketing challenges, and possible ways forward.

A Cultural Keystone on the Decline

The Mahua is a slow-growing, deciduous tree that yields thousands of sticky, sweet flowers in the summer, aligning with the agricultural lean season. For generations, Mahua has sustained households in Bastar, earning motherly reverence in Adivasi cosmology. The trees are considered sacred, housing deities and ancestors, and are never supposed to be cut or shaken (Hiwale, 2015). Families wait for their trees to shed flowers and seeds naturally. During the two flowering months, the women rise early, walk tiring distances to their trees, gather flowers off the ground from morning till noon, sun dry, and store them. These flowers become snack balls, are brewed into fermented teas, and most widely, distilled into a clear liquor that sanctifies festivals and fuels tribal hospitality. Small quantities of the flowers are sold weekly at haats, with earnings spent on groceries and essentials. The liquor is bottled and stored for consumption and sold within villages year-round.

Many villagers, however, report that trees are now yielding fewer flowers than before. Scientific evidence of Mahua’s declining productivity or systematic records tracking tree survival or regeneration in Bastar are scant. But respondents across age groups note that flowering has been steadily declining for at least five to ten years. Village youth recall childhood seasons when flowers were so plentiful they could not be fully gathered, consumed, or stored.

These trees are many decades, maybe even a century old, and communities are familiar with their natural cycles and occasional off-years. The issue, they say, is persistent: flowers are fewer, naturally regenerated saplings are rare, and those that sprout often die after just a few feet of growth. Seed availability has also dropped, reported the collectors and traders. Climatic disruptions such as unseasonal rain and cold spells were cited as another factor, causing early flowering and keeping the flowers unshed from the trees till they shrivelled. Households have gone from gathering a couple of quintals to only a few baskets. In response to reducing availability, many have abandoned the traditional practice of burning the forest floor to clear the ground before collection as it is now thought to harm regeneration. Cultural beliefs though still discourage manual plantations that could supplement natural regeneration.

This ecological dimension poses long-term challenges for Adivasi livelihoods and demands rigorous study. Yet, the immediate economic systems that govern Mahua affect communities far more urgently.

The Markets and Interventions at Play

Trade scene at the haat, showing the stocks of Mahua flowers, millets, tamarind at Kodenar

Trade scene at the haat, showing the stocks of Mahua flowers, millets, tamarind at Kodenar

The haats are the primary platform for Mahua trade. Collectors sell dried flowers to traders, who take them to the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) mandi where they are auctioned to wholesalers or cold storages. Traders then repurchase them during the off-season and sell them back to Adivasis at marked-up (often double the original) prices. Many traders have worked the same haats for years and share long-standing relationships with villagers. Some go directly to the villages, trading Mahua for groceries like potatoes, onions, and salt, via volumetric exchange – one paili (local unit ~1.3kg) of flowers for one paili of potatoes. This is a highly convenient arrangement only prevalent in villages characterised by poor connectivity and haat frequency.

There is also the state facilitated market for better quality Mahua. Following the recommendations of the Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development Federation of India (TRIFED), a national ‘minimum support price’ (MSP) for Mahua was introduced in 2018 (PIB, 2018). The 2024–2025 notification of the Chhattisgarh Minor Forest Produce Federation quotes an MSP of Rs 30–33 per kilogram of dry flowers. Although the MSP is not legally mandated, it is enforced within the more regulated procurement pathways through the Van Dhan Vikas Kendras (VDVK) or CGMFPFED (Chhattisgarh Minor Forest Produce Federation) centres at the MSP which trade food-grade Mahua (CGMFPFED, 2023). These flowers are collected hygienically using nets and dried in meshed frames or solar dryers. This system could in theory help collectors bypass private traders entirely. State level food-grade procurement data show that 2,500 quintals of Mahua were purchased from self-help groups (SHG) across Chhattisgarh in 2022–23 at Rs 45 – 50 per kg, and 700 quintals the following year. This regulated collection has also been supplemented with value-addition by both the public and private sectors.

While the state has been marketing value-based Mahua and other Non-Timber Forest Produce (NTFP) products under the brand Chhattisgarh Herbals since 2021, Bastar Foods Firm, established in 2018, pioneered NTFP product development in Chhattisgarh. They work with SHGs across 20+ villages, paying Rs 45 per kg. They have developed laddoos, teas, cookies, and pickles, aiming to shift Mahua’s reputation from liquor to a nutritious and versatile food product. In 2024, they partnered with a London-based firm to expand spiced Mahua tea production for export, procuring over 70 tonnes. Like CGMFPFED, they use an order-based production and payment system.

However, a couple of enterprises cannot make a major dent in the 5 lakh quintals of Mahua flowers Chhattisgarh produces annually. Combined, the approximately 3,500 quintals are estimated to tap into less than a per cent of the yearly quantum and an equally small fraction of people benefit from these systems. In 2022–23 just 2,200 SHG collectors out of the over 70 lakh Adivasi and forest-dependent population participated in state procurement.

So despite the prevalence of new welfare-based interventions, their minimal scale means households are still largely dependent on haats. Very few traditional Mahua collectors seem to be aware of the concept of MSP or the arbitrary demand for food-grade Mahua at collection centers. Moreover, these centres and training efforts are concentrated in Mahua-rich districts like Dantewada and Manendragarh, leaving many other areas underserved. This is a gap that is yet to be reported on.

Most villagers quoted MSP-commensurate payments at the haats, but traders sometimes reportedly get away with offering as low as Rs 25 per kg when the auction rates drop. At such fluctuating, low prices, and with shrinking yields, Mahua has ceased to bring in adequate revenue as it once did. Modern storage methods have added to the issue. Traditional bamboo drums could apparently keep Mahua flowers dry and unspoiled for nearly a year. Now to store the smaller quantities, they opt for plastic drums and sacks that cause spoilage within four months–forcing quick sales. Costlier flowers from cold storage often circle back to Adivasis, allegedly treated with chemicals to preserve freshness, but potentially affecting the quality and extraction of liquor. As the ultimate consumers, they must pay more for degraded stock, and liquor that normally sells for Rs 50 per litre can drop to half that price if customers are unsatisfied.

How are Communities Adapting?

Faced with dwindling yields, volatile markets, and slow-moving, exclusionary interventions, communities are employing different strategies to sustain livelihoods that come with their own tradeoffs.

Direct Sales

Some villagers engage in sales to individual customers, marking up prices by 50–100 per cent and earning more despite lower demand. However, direct market sales demand time and labour that many households cannot spare. Women, who handle most Mahua-related work, are already burdened with domestic tasks. Motorbikes are becoming more common among younger men, but most still rely on irregular and expensive privately owned public transport like buses and vans to reach haats and individual buyers.

Negotiating and Bypassing

When traders exchange groceries for flowers, collectors try to negotiate for additional quantities by asserting the value of their produce. Others bypass traders altogether by taking only higher-value products like tamarind to the mandis. Both approaches, however, are limited by convenience and access: households prefer quick exchanges even at lower returns, and long distances remain a significant barrier despite gradual improvements in vehicle ownership and connectivity.

Liquor Production and Diversification

While traditionally, Mahua was consumed in tea, snacks and meals, most households have now fully shifted to Mahua liquor production. One bottle can yield 30–60 per cent more profit over selling a paili of flowers. Households may earn between Rs 1,500 and Rs 15,000 annually from liquor, which is a significant income boost in communities where most are below the poverty line. But this option is not viable for everyone. Households with fewer trees or are primarily dependent on Mahua must spend more on purchasing flowers and putting in high effort for limited profit.

This practice also poses legal risks. The Chhattisgarh Excise Act of 1915 allows households to brew only up to five litres of country liquor, officially prohibiting sale. Yet Mahua liquor is freely traded within and between villages as a major livelihood activity. Sporadic enforcement, sometimes involving confiscations, creates uncertainty within policy that already seems inequitable—Indian Made Foreign Liquor (IMFL) is commercially produced under regulation, while traditional Mahua liquor remains criminalised, pushing producers into a legal grey area. Faced with these constraints, households seek ways to reduce their dependence on liquor sales for cash needs.

Income diversification was widely prevalent in households, through farming, wage labour, employment or small businesses, allowing them to reserve liquor purely for household consumption needs. Yet, respondents feel that the liquor taking centre stage is eroding Mahua’s cultural significance, with a lack of time and knowledge of other traditional recipes. Further, they say it is leading to a loss of nutritional benefits they once gained through consuming the whole flowers.

Potential Ways Forward

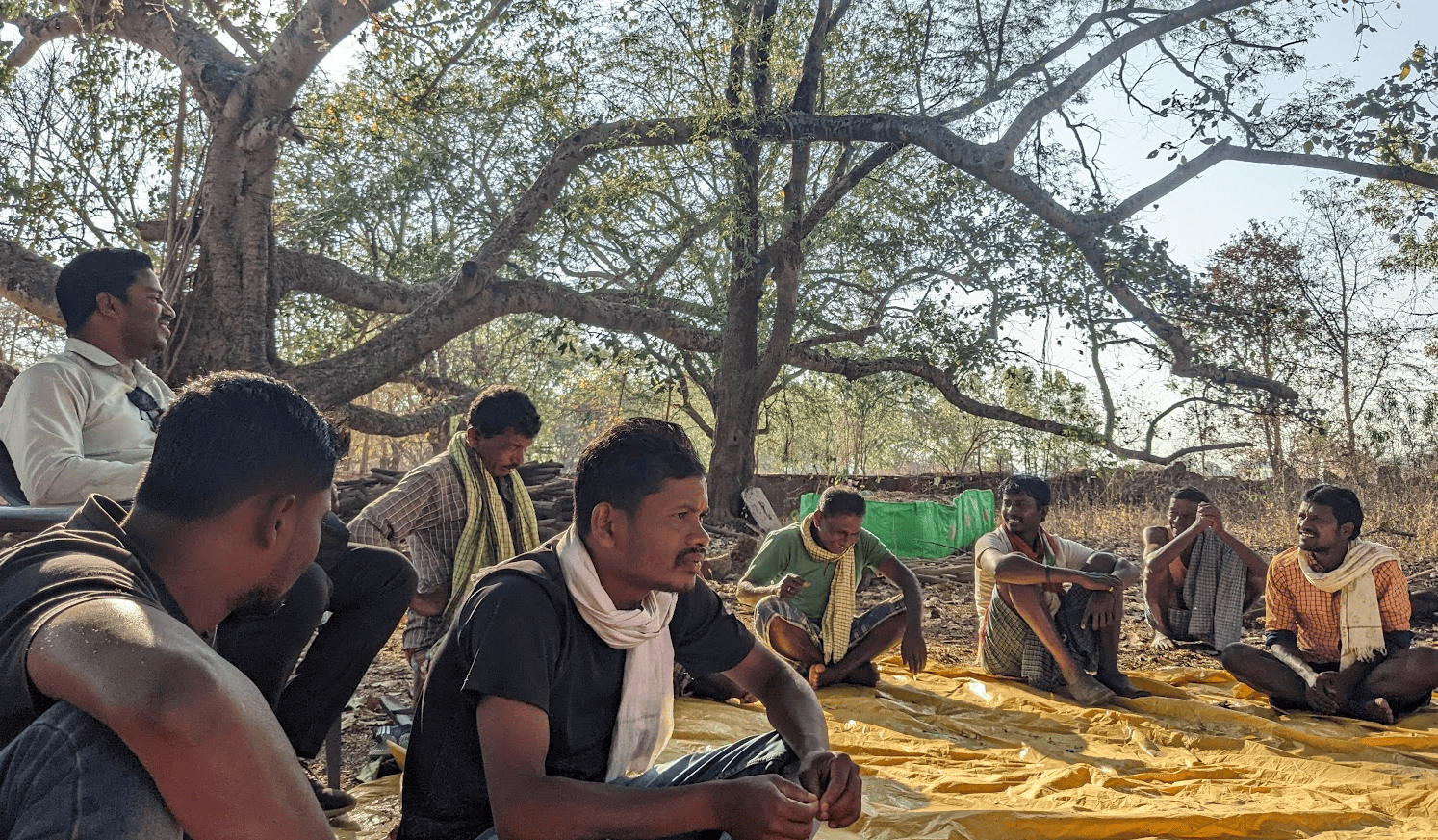

A Gondi couple collecting fresh Mahua flowers, Badekakloor

Following the recognition of community forest resource rights (CFRR) in Maharashtra under the Forest Rights Act 2006, many Gram Sabhas in eastern Maharashtra have begun to form federations for collective marketing of tendu (Diospyros melanoxylon) leaves, a high-value NTFP (Date and Lele, 2025). Similar initiatives for NTFPs and eco-tourism too have been undertaken in Odisha (Down to Earth, 2024) and Chhattisgarh (CFR-CII website, 2024). Unlike tendu, sal and tamarind, most Mahua trees in these areas are privately owned, which could make collectivisation and federation challenging. So, organizing collective marketing without disrupting community life is key.

As the Ministry of Tribal Affairs reaffirms that, through their CFR Management Committees (CFRMC), Gram Sabhas hold sole authority to formulate community resource management plans for Chhattisgarh (Down To Earth, 2025), they could play a convening role for Mahua by pooling small household quantities, negotiating shared storage, sale arrangements, vetting external partnerships and promoting tree management. The three villages in this study secured their CFR titles in 2022–23, laying the groundwork for such initiatives.

While plantation drives are already underway in some villages they could gain traction if reframed as cultural rituals with elders selecting sites and heading ceremonies to restore Mahua’s place in community identity. Community based monitoring and participative ecological studies of the plantations will be essential for their success and replication. Since older trees may not revive and new saplings could take about ten years to flower, quantity improvement must be preceded by better financial and information systems.

Strengthening existing structures of microfinance SHGs by tying them back to resource management plans could mobilize savings for long-term regeneration efforts, while offering short-term credit to reduce distress sales. Many collectors still depend on traders for weighing and price calculations. Simple haat tools like MSP price boards, paili-to-kilo conversion charts endorsed by Gram Sabhas could improve transparency and prevent any inadvertent undervaluation. But true bargaining power comes from collective negotiation, which the local governance is positioned to facilitate.

For large, scattered villages, hub-and-spoke models with community resource persons could bring awareness and training closer to households. Women, though less informed, expressed strong interest in learning value-addition skills, provided training was accessible and did not disrupt household routines. Entry points to capacity building might begin with collectivising produce sales that do not stipulate specific processes, before graduating to food-grade Mahua handling and value-addition that prioritises women’s participation. Diversifying away from liquor could reduce their vulnerability to legal enforcement and improve access to nutritional products.

Over time, Gram Sabhas with stronger planning capacity could also draft proposals to access tribal development funds under Article 275(I) for decentralised cold storage, allowing households to hold stock longer and sell at favourable prices. Reliable procurement and payment systems from both state and private enterprises could then follow to create a sustainable livelihood for the communities. As seen in Madhya Pradesh, when collectors receive adequate institutional support the quality and supply of Mahua is improved such that it is said to be the best in India, attracting huge export deals (The Free Press Journal, 2023).

Neither the flowers nor the markets alone define Mahua’s story in Bastar. It is the entanglement of ecology, culture, livelihoods that defines it. The Adivasis’ vulnerability shapes their inclinations towards what’s immediate and familiar. Until research builds evidence for stronger policies and interventions, which are tailored to work within this reality, through reliable and well-represented grassroots systems, the shrinking heaps of Mahua in the haats will continue to tell a larger story of the simultaneous decline of the iconic tree and livelihoods that revolve around it.

References

Anon. 2023. “Bhopal: 200 Tonnes Mahua to Be Exported to London.” The Free Press Journal, April 17, 2023. https://www.freepressjournal.in/bhopal/bhopal-200-tonnes-mahua-to-be-exported-to-london?utm. Accessed September 7, 2025.

CFR Central India Initiative (CII). Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE). 2025. “Tiriya’s Journey: From Forest Rights to Forest Stewardship.” https://cfr.atree.org/blog-two/. Accessed September 7, 2025.

Chhattisgarh State Minor Forest Produce Federation Limited. 2023. “Notice for Sale of MFPs at fixed and retail price”. Samvad Portal. Government of Chhattisgarh. https://samvad.cg.nic.in/GetFile.aspx?Id=9282a59b-e43f-4909-bba4-e05bd98f0d2b. Accessed September 7, 2025.

Date, Anuja Anil, and Sharachchandra Lele. “Marketing of NTFPs by forest-dependent communities in Maharashtra, India: Alternative models for state support.” Forest Policy and Economics 178 (2025): 103584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2025.103584

Hiwale, S. 2015. “Mahua (Bassia latifolia Roxb.).” In Sustainable Horticulture in Semiarid Dry Lands. Springer, New Delhi. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2244-6_18.

Ministry of Tribal Affairs. 2018. Press Information Bureau Release, December 27, 2018. https://www.pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1557528. Accessed September 7, 2025.

Panda, B. B., P. K. Mishra, and R. Thakur. 2010. Report of the Study on Mahua Sub Sector. The Livelihood School, Bhopal. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/36635221/study-on-mahua-sub-sector-cgsirdgovin.

Pani, Chitta Ranjan. 2025. “MoTA Champions Tribal Autonomy, Upholding Gram Sabha Rights in Chhattisgarh’s CFR Management.” Down to Earth, August 25, 2025. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/forests/mota-champions-tribal-autonomy-upholding-gram-sabha-rights-in-chhattisgarhs-cfr-management. Accessed September 8, 2025.